Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Apologies and Excuses

Just a quick post to say that I haven't abandoned the old blog.

It's partly laziness, partly busyness. Much of what is happening leaves me speechless, but at other times there seems so much to say that I feel like the proverbial ass who starved to death because he had no sufficient reason to choose between two equidistant bales of hay.

And it's not like the world is suffering from any lack of talk.

So, to the happy few (or perhaps the increasingly-unhappy fewer) I will try to get back on a regular schedule of posting in the fall.

Ave, atque vale.

Saturday, July 8, 2017

Est-ce que ceci tuera cela?

I have been reading Victor Hugo's Notre Dame de Paris. In a 2009 post, having just completed Hugo's Les Misérables, I noted Hugo's love of digressions. Notre Dame isn't as chock-full of them as Les Mis, but Hugo engages in some major frolic and detour in the second chapter of Part Five in a section entitled "Ceci tuera cela."

"This will kill that." The printed book will kill architecture.

Here Hugo exemplifies a favorite approach to discursive writing: take a simple, smart observation and then run it into the ground.

It is a commonplace, I think, to see the great churches of medieval Europe as the books of the illiterate, the great bibles setting out, in light and sculpture and music and stained glass, the stories and dogmas of the faith. I say it is a commonplace because I'm not sure that it was so in Hugo's day. And though Hugo himself was very much the advocate and harbinger of a liberal and progressive era, he was unusual in his appreciation of the beauties of the Gothic, and arguably working against his progressivism in practicing, and arguably, in France, inventing, the genre of the historical romance.

But he sees the book and the edifice in opposition. And he puts the observation in the mouth of Claude Frollo, his clerical villain, foreseeing the satirical jibes of Erasmus eliding into the unprecedented waves of polemic and counter-blast of the Protestant Reformation, all made possible by the printing press. It is an accurate observation, but it stands independent of the status of architecture.

And obviously building didn't stop. So Hugo turns the argument from the destruction of architecture to its decadence, asserting the inferiority of the Renaissance style to the Gothic (in this he was famously seconded by Ruskin). The great domed churches he reduces to a formula, "the Pantheon heaped on the Parthenon," again and again and again, paying tribute to Michelangelo's St. Peters as the one work of genius that inspired the series of imitations. But the formula, however clever, hardly accounts for the originality of the centuries of Renaissance and Baroque and neo-classical work that followed.

Hugo also can't help but acknowledge the monumental works of literature that tended to define their culture. Are the great epics of Homer somehow less constituative of the Greek spiriti than the Parthenon?

It's in that ambiguity of "press" and "book" that Hugo arguably comes a-cropper. There is a real change between the medieval and modern world that is less the case of press destroying architecture than of an explosion of options and expressions that makes the relative uniformity of the pre-medieval world no longer an option. The pre-modern world tended to have what can be called a narrower canon, a more manageable set of fundamental writings, a characteristic arguably attributable in part to the limited dissimulation of written work in manuscript. And similarly, the magnificent architectural monuments of the pre-modern world were part of a comparably limited "canon." Medieval Paris was full of churches, but each represented more than a generation of devoted work. Our modern building can't shoot up as quickly as an edition of a new book can be printed. But it's difficult to think of any architectural project of the last four hundred years that would have been undertaken if, like Paris' Notre-Dame, or Florence's Santa Maria di Fiore, its completion was not expected for more than a century.

The technical power of the modern world makes more possible faster. Whether more and faster leads to better is an open question. Happily, the book never killed the edifice. But both acquired an arguably less massive inertia, reflected in the accelerated series of revolutions that perhaps best define the modern world.

Saturday, May 27, 2017

Our "Muslim Problem," Part Two: The Religion of Islam

Before beginning this section I think it would be helpful to define a few words.

First, "orthodoxy" and "heresy." Both words carry connotations of praise or blame that I'd like to avoid, if possible. The point I'd like to stress here is that neither means anything if asserted without reference to a specific religious group. To take a simple example, to say that "God has an only-begotten son" is orthodoxy in Christianity and heresy in Judaism or Islam. In other words, to assert that something is orthodox or heretical only makes sense by saying that it is so in relation to some particular set of doctrines.

By the same token, though the terms "corruption" and "reform," in the context of religion, both refer to a change, the one refers a blameworthy change with respect to orthodoxy, one which distorts and denies orthodoxy, and the other refers to a salutary change with respect to orthodoxy, which restores orthodoxy and corrects heresy. Whether the "new thing" restores or obscures orthodoxy depends, naturally, on what one thinks orthodoxy is in the first place.

So what exactly is Islam? It is obviously a "World Religion," quite a major religion with something over a billion adherents at last count. Like the other two dominant Western world religions, Judaism and Christianity, it has an ascertainable set of dogmas (one God, creator, transcendent, as proclaimed by a final prophet, Muhammad), a set of holy writings (most importantly, the Qur'an), and a distinctive law, ethics, style of worship and organization. Like most major religions it has some major divisions (the Sunni/Shi'ite split) and innumerable smaller ones, most within and among the "big two."

But to simply list the distinctive characteristics of Islam can obscure what I think is most germane to the inquiry here, how its adherents should be viewed as Western and Islamic civilizations come to intermingle.

My central point is that, from the point of view of Christianity, Islam is best understood as a heresy, and that, from the point of view of Islam, both Christianity and Judaism are best understood as corrupt forms of an Islam that has existed since the time of the biblical Patriarchs, restored and reformed by Muhammad.

This relationship is sometimes papered over with the innocuous and accurate-as-far-as-it-goes description of Judaism, Christianity and Islam as the "Abrahamic religions." All do indeed look back to the figure of Abraham as an exemplary figure; but they also all three look back to Noah, and the antediluvian patriarchs, and Adam. So in a sense to suggest that Abraham is a uniquely uniting figure can be misleading. More accurate is to see how Moses is the determinate figure of Judaism (revered by Christians and Muslims), Jesus is the determinate figure of Christianity (revered by Muslims), and Mohammed the determinate figure for Islam.

So though they are far from constituting a single religion, they do constitute three singularly similar religions, with Islam closer, religiously, to Judaism than Christianity, just as the careers of Moses and Muhammad, as political leaders and lawgivers, are more similar to each other than to the career of Jesus.

Christianity is arguably distinctive in having a soteriology that presumes the existence of a divine law that has itself become a hinderance to the reconciliation of God and man. To put it another way, in Judaism and Islam the tension beween law and grace are less central than in Christianity, where the redemptive death of the Son has a unique role. But Judaism, even before the advent of Christianity, gave rise to the prophetic movement, as a critique of the law and the cult that is the object of so much of the law, and after the destruction of the second temple a long and complex series of legal and theological developments continued to give rise to a way of life rooted in the law, but by no means merely "legalistic." Similarly, in Islam, the law there newly proclaimed, not radically different in its ethical standards from Jewish law, is subject to a God who is repeatedly "the compassionate, the merciful," and whose severe judgments on lawbreakers do not preclude God's continuing willingness to forgive. As in Judaism the formal priority of the divine law is mitigated by a long and subtle history of legal, theological and philosophical development. There is also the express appeal to the heart in movements such as Sufism, an appeal whose point is not an opposition to the law, but, in a figure such as al-Ghazali, having a "completing" effect on one already a formidable shaper of law and philosophy.

Despite popular claims, I don't see great discrepancies between Islam's ethics and those of Judaism and Christianity. There are differences, of course. Islam allows limited polygamy, for instance, but the practice is hardly widespread, and certainly less common than the "serial polygamy" of marriage and divorce and re-marriage so common in contemporary Christianity. Some see in the Qur'an a violent attitude to non-Muslims, and I am familiar with the passages that give rise to those concerns. But I also can't help but note that there are similar passages in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures that with similar justification have grounded polemics contending that Judaism and Christianity are inherently violent and intolerant. But in practice, so far as I can tell, ordinary Muslims try to be honest, generous, hard-working and forgiving, pretty much as ordinary Jews and Christians do.

The conclusion of this is that the religion of Islam is sufficiently similar enough to the religions of Judaism and Christianity that I do not see that there is any religious impediment to Jews, Christians and Muslims living together in peace as citizens of religion-neutral republics. Those differences that are undoubtedly there need not necessarily lead to attempts to dominate. Of course religious differences will give rise to political differences, but the resolution of those differences by means of representative government with fundamental rights of speech, press, assembly and religion protected, means that those differences need not undermine the common polity.

But, one might respond, Islam is more than a religion. It is also a polity, a culture, a civilization, and that fact arguably creates problems above and beyond those posed simply by the religion. It is to that contention I hope to turn in the next installment of this series.

Monday, March 27, 2017

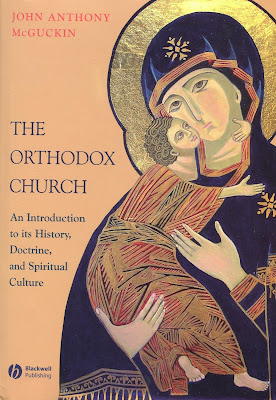

Fr. McGuckin's Orthodox Church

This is a book I can certainly recommend, keeping in mind my own very limited interaction with Orthodoxy. A few years ago, essentially on a whim, I attended a local Divine Service. It was an ordinary Sunday, at a small church, with fifty to sixty participants that morning. The language was English, those who welcomed me were happy to have a Catholic visitor (the greeter was himself a former Catholic), and the liturgy, simple as it was, was sublimely beautiful. A Catholic's relationship to Eastern Orthodoxy is rather unique; the Catholic Church recognizes as valid all the Orthodox sacraments, though that recognition is not reciprocal. So my relationship was not one of hostility, or competitiveness, but of curiosity about a polity that, from a Catholic perspective, has been in schism for a millenium or so.

Fr. McGuckin's book pretty thoroughly covers the bases for an overview. It begins with a history of the Church, first tracing the first centuries of full communion between Latin West and Greek East, then summarizing the subsequent history, giving sketches of each patriarchal, autocephalous and autonomous Church within the single communion. Some of these sketches can be rather dry, but they are essential to understand the present position of Orthodoxy, especially the complex jurisdictional status of "new lands" such as the United States.

He then discusses the doctrinal foundation of Orthodoxy, looking first at what is held authoritative, then discussing, in separate long chapters, "theology" (the Trinity and the incarnation) and "economy" (teaching regarding salvation, or deification).

One of the differences between McGuckin's account, and that of Ware (as I admittedly dimly remember it), is that Ware very much emphasized the closeness of Orthodoxy and Catholicism, whereas McGuckin tends almost exclusively to contrast Orthodoxy with "the West" or "the Latins." There are, of course, good reasons for finding similarities between Catholics and Protestants, which can broadly be summarized as the "Augustinian heritage." But my sense is that McGuckin goes too far in emphasizing Catholic/Orthodox difference on questions where the two communions stand far apart from Protestantism: the authority of Holy Tradition, the importance of the episcopate, the centrality of the sacraments and sacramentals, the reverence paid to the Mother of God and the saints, and the use of images in prayer and worship. Don't misunderstand, he isn't polemical, and part of this sense of distancing comes from what exactly he is doing, not writing a treatise on ecumenical relations between Catholic and Orthodox, but summarizing Orthodoxy in Orthodoxy's own terms. Thus, the delineation of Orthodoxy in distinctively Orthodox terminology does help to see genuine differences, even if, from a Catholic perspective, this may appear to make of those differences more of a gulf between the two communions than in fact actually exists.

Fr. MeGuckin does a very good job of reviewing the hierarchy of sources of orthodoxy: scripture, the seven great Councils, the very rich forms of worship and prayer, and the writings of the Fathers, the monastics and the saints, and he conveys well the sense that these things are distorted if considered separately, that scripture is not an ancient anthology, not to be considered primarily as a book, but as it is encountered in the Divine Liturgy, as it is reflected in the lives of the saints and in the continuing unfolding of Holy Tradition.

He is most disdainful of the scalpel that Western Christians have taken to scripture using form-historical criticism, seeing it primarily as a massive exercise in missing the point. And on that issue I do in fact have much sympathy with him. Biblical studies, in the West, have tended, in the last century and a half, to focus almost exclusively on separating the "genuine," the "historical," from the "priestly," or "mythological," or "pre-scientific." The more sophisticated proponents of these studies have, in fact, not necessarily privileged the former over the latter, but the popular view that has trickled down to the general public is as a debunking of scripture, and I have to say that, for all its interest and continuing novelty, it seems to me to have been largely spiritually sterile. At the same time I suspect that Orthodoxy's lack of engagement with these studies has more to do with Orthodoxy's having been suppressed and isolated for so long, and that, in some form or fashion, its welcome resurgence will require it at some point to take some more articulated position with respect to the critical acid of modern doubt.

I found the best part of the book to be the review of "theology," the Orthodox articulation of the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation, perhaps because those topics are arguably held most closely in common between East and West. Fr. McGuckin reviews this teaching with extensive quotations from St. Irenaeus of Lyon, St. Cyprian of Carthage, St. Athanasius, St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory the Theologian (a/k/a St. Gregory Nazianzus), St. Cyril of Alexandria and St. Gregory the Dialoguist (a/k/a Pope St. Gregory the Great), all of whom are also honored in the West as pillars of the patristic age. And Fr. McGulkin does not follow the lead of some contemporary Orthodox in reading St. Augustine out of the Eastern tradition. He correctly sets out how a number of differences between East and West come from positions which, if not entirely Augustinian in origin, certainly have come to prominence in the West due to Augustine's overarching prestige. But McGuckin nevertheless always insists that the Blessed Augustine is an Orthodox father whose particular teachings, like those of every other Orthodox father, are never infallible or beyond being rejected or found wanting.

By contrast I was disappointed in the next section on the economy of salvation. It set out clearly the Eastern notion of deification, but as opposed to a rather woodenly presented Western conception substitutionary atonement (a contrast minimized by the honest admission that the dominent Western models of salvation do indeed have some scriptural and patristic support). There was a great deal on the importance of a correct ecological relationship to the world and to nature, not something that I would disagree with, but I was not convinced that such a concern has particularly distinctive or ancient roots in Orthodoxy. All in all what was most noticeable was the considerably lesser citation to the great Orthodox sources compared to the prior section.

There follows a section on what the Orthodox tend to call the greater and lesser mysteries, which Catholics call the sacraments and the sacramentals. McGuckin thoroughly runs through the differences in custom and conception, though my general sense is that the differences are minor and that the inevitable superiority that McGuckin finds in admittedly admirable, beautiful and spiritually profitable Orthodox approaches comes to sound a little perfunctory.

The long section on Orthodox liturgy and prayer is filled with numerous and generous quotations hinting at the flavor of Orthodox worship. My only quibble with this section is that, from my quite limited experience (see the second paragraph above) the bare words on the page in fact fall far short of conveying the beauty of Orthodox prayer in the Divine Liturgy. But I recognize that a book can only do so much.

Next there is a brief but important section on Orthodoxy and the political realm, taking the West to task for developing the papal monarchy, and strenuously denying the appropriateness of the term "Caesaropapal" for the place accorded the Byzantine emperor. Here, again, the Eastern and Western approaches seemed as described more similar than distinct, at least insofar as the post-Constantinian, pre-disestablished Church asserted the divine authority of both political and religious rulers, even while drawing lines between secular and sacred authority and asserting the superiority of the sacred.

While it is easy for those of us in the West to be scandalized by the giving of titles like "Equal of the Apostles" to Constantine, the foundation of the Western Empire under Charlemagne operated under many of the same assumptions that it was appropriate to recognize a particularly Christian ruler as heir of the Caesars with the special calling to care for the Church. That notion didn't die in the Reformation, with Henry VIII most prominently claiming the privileges of Emperor and a headship of the Church in his realm. The Western Empire, of course, didn't end until the Napoleonic wars, and a number of Christian monarchs in the West claimed privileges over the Church that only in the last two centuries have been abolished. So, in that sense, as well, the history of the East doesn't seem that strikingly different from that of the West, and there seems to be as little desire for the re-establishment of the Christian Caesar there as here.

Finally there is a section on Orthodoxy and certain modern social issues, such as women's emancipation and sexuality. Here there was not so much as a description of Orthodoxy's stance as the review of those issues by one Orthodox priest--Father McGuckin. I didn't find myself disagreeing with much that he said; I just wasn't entirely sure to what extent it represents Orthodox thinking on these subjects. Father McGuckin is a convert, an Englishman (I think) and a faculty member at Union Theological Seminary and Columbia University. I don't list those things as drawbacks, only as possible limits on the extent to which Father McGuckin may be representative on these issues. Insofar as his stance seeks a balance between a charitable progressiveness and tradition, it reads, to me, much like the pronouncements's of Vatican II's Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. Again, I don't find that a basis for disagreement. I simply suspect that some Orthodox might find him a little too accommodating.

I hope I've conveyed the sense of recommending the book. No single volume obviously can be the last word on such a subject. And I found it interesting that, at the same time that I was finishing up this book, I happened to run across and purchase the Pleiade edition of the works of John Calvin. Having been raised Presbyterian, and having audited a course on Calvin, my third year of law school, at the nearby Divinity School, I've had a long relationship with him, and, in many ways, he represents the polar opposite of Eastern Orthodoxy.

I discussed above McGuckin's description of the Orthodox conception of the bible, not so much as a stand-alone book, per se, but as a series of sources integrated into the tradition. Calvin can be taken as representative of the Western approach, at least since the Renaissance, of giving the bible the treatment that the earlier Renaissance humanists gave the received classics upon which they hoped to refound intellectual life. Having been purified of extraneous matter the Christian scriptures were to become the standard for a wide-ranging critical role far beyond the literary standard-setting of a Cicero or a Livy.

For all of McGuckin's disdain of Western medieval scholasticism, medieval Catholicism's relative lack of 'bible-centeredness" makes the East and West in those centuries look much more similar than in the modern world. There was always an assumption that East and West could be reconciled, even with many non-theological stumbling blocks, like the Fourth Crusade. In some ways the ushering in of the Age of the Book in the Renaissance created a greater cultural divide. The question, I suppose, as the Book gives way to the Net, is whether that will lessen or heighten the tensions between East and West.

Sunday, February 19, 2017

Our "Muslim Problem," Part One: Overview

I have long intended to write something about Islam and the contemporary West. Recent events have suggested that perhaps now might be a good time.

I have no particular expertise in the subject, only what I know of history, and my own limited experiences.

I put the "Muslim problem" in "scare quotes" because some recent reading from the early twentieth century, where a widespread concern with what they called the "Jewish problem" was evident. What to do with them? How do they fit in, these non-Christian interlopers, these wealthy money-lenders, these superstitious, clannish Eastern strangers with their own Law and their own language--in short, how to deal with these people whose whole existence contradicts the contemporary notion of the integral, ethnic Nation?

Most people with any sense of decency look back at that time with shame and alarm for what we know followed. Our "Jewish problem" turned out to be mostly a problem with ourselves, and my general take is that our "Muslim problem" is largely little different, though the two situations plainly are not entirely the same.

Our modern anxiety stems from the unavoidable fact that the boundary between Islam and the West becomes less distinct year by year. There was always conflict along the boundary of the two civilizations, and the boundary sometimes moved dramatically. But the two civilizations did not mingle in any significant fashion until the imperial West first conquered large portions of the Islamic world, beginning with Napoleon, followed by a significant, if still relatively small, intermingling of the populations as imperialism retreated.

What that means is that the violent disorders that have characterized the middle east and southern Asia over the last fifty years--disorders for which the Western powers plainly share some significant part of the blame--are spilling over into the West. And that in turn has given rise to a widespread fear that that exported violence is not simply the "outskirts" of the current wars, but somehow intrinsic to Islam, that they are skirmishes in an ongoing war between Islam and the West which has to be prosecuted by punitive measures against Muslims in the West and by barricading the borders.

So what I'd like to do is look at the question in four further posts. The first will look at exactly how Islam should be understood as a religion. The second will consider Islam as a civilization. The third will look at the question from the perspective of what I think is demanded of a Christian, one who is committed to following the teaching and obeying the commandments of Jesus Christ. The fourth will look at the question from the perspective of American values; that is, those American ideals embodied in our founding documents and cultural images.

Saturday, January 21, 2017

Revolt in the Desert

A hundred years ago the First World War was raging. Our first mental image of that conflict is probably the landscape of trench warfare in Western Europe: Unbroken ditches running mile after mile, no-man's-land, blighted landscapes, barbed wire, and waves of doomed men going over the top.

Yet there were other theaters in that war, no less brutal, no less senseless, but whose foreignness won them a pass in the contemporary imagination. I'm thinking, of course, of the Arab Revolt, a movement encouraged by the British against Germany's eastern ally, the Ottoman Empire of the Turks, chronicled most famously in T.E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Lawrence remains an enigma. Solitary in life and unmilitary in demeanor, he took a new name and sought anonymity after publishing his great memoir, completing his translation of the Odyssey just before dying in a motorcycle accident on a quiet English road.

A couple of decades ago I read Revolt in the Desert, Lawrence's abridgment of Seven Pillars. He lost his first manuscript of Seven Pillars, and when rewritten made it available only in a severely limited edition. Its reputation created a demand that Lawrence answered with Revolt, a version that read like a traditional account of a military campaign. What was left out of Revolt, and what makes Seven Pillars such a compelling read, is Lawrence's self-revelation--not only his eccentric observations on Arab life, but his whole consciousness of duplicity in encouraging one people's revolt for his own people's advantage. James Morris has called shame the leitmotiv of Seven Pillars, and that sense of play-acting in a deadly serious game permeates the book with an omnipresent unease.

A soldier, but also an artist, as noted by Jean Villars at the beginning of his biography of Lawrence:

Dans la galerie des grands hommes, Thomas Edward Lawrence—le colonel Lawrence—est l’un des rares, peut-être le seul, á avoir été á la fois un chef de guerre et un artiste.

Seven Pillars reads much of the time like other classics of exploration. It describes, day by day, travel through the desert: the geography of well and oasis; the composition of ground: sand, slate or flint; the hills and the wadis; the unrelenting sun. In this it is reminiscent of books like Burton's Lake Regions of East Africa, or Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle (an expedition as much geological as biological). Here is Lawrence observing the difference between male and female camels:

"Arabs of means rode none but she-camels, since they went smoother under the saddles than males, and were better tempered and less noisy: also, they were patient and would endure to march long after they were worn out, indeed until they tottered with exhaustion and fell in their tracks and died: whereas the coarser males grew angry, flung themselves down when tired, and from sheer rage would die there unnecessarily."

These kinds of narratives make it a classic of travel writing. But it also a war memoir:

"Blood was always on our hands; we were licensed to it. Wounding and killing seemed ephemeral pains, so very brief and sore was life with us....Bedouin ways were hard even for those brought up to them, and for strangers terrible: a death in life. When the march or labour ended I had no energy to record sensation, nor while it lasted any leisure to see the spiritual loveliness which sometimes came upon by the way. In my notes, the cruel rather than the beautiful found place....Our life is not summed up in what I have written (there are things not to be repeated in cold blood for very shame); but what I have written was in and of our life. Pray God that men reading the story will not, for love of the glamour of strangeness, go out to prostitute themselves and their talent in serving another race."

That last line highlights the irony of Lawrence's contemporary fame. He is best known from David Lean's extraordinary film "Lawrence of Arabia." In the film he is presented as virtually taking leadership of the Arab Revolt, a textbook instance of what is sometimes called the "Mighty Whitey" trope. In his memoir Lawrence, not an extraordinarily modest man, always emphatically insists that he was a collaborator in an operation that he in no sense led.

So the film tends to make Lawrence an unabashedly romantic character, a role he sincerely tries to shun in his memoir. But it must be said that the film does convey some sense of Lawrence's inner doubts, often amounting to a kind of agony.

"[T]he effort for these years to live in the dress of the Arabs, and to imitate the mental foundations, quitted me of my English self, and let me look at the West and its conventions with new eyes: they destroyed it all for me. At the same time I could not sincerely take on the Arab skin: it was an affectation only. Easily was a man made an infidel, but hardly might he be converted to another faith. I had dropped one form and not taken on the other, and was become like Mohammed's coffin in our legend, with a resultant feeling of intense loneliness in life, and a contempt, not for other men, but for all they do."

Lawrence wrote at a time when Arabia was far more exotic than it is now. Our entanglement with the middle east is not only more pervasive than it was a hundred years ago, but the terms are profoundly different. One of the perhaps surprising characteristics of Lawrence's war was the tangential role of Islam. This was a conflict between Arabs (allied with English) and Turks (allied with Germans). The creed which Lawrence preaches is Nationalism, a cause nipped in the bud after the war by the French/English carve-up of the middle east, and made largely irrelevant today by the overriding significance of the struggle between Sunni and Shi'ite interests (and, of course, the continuing resentment over Israel).

Another contemporary facet of Lawrence's story is the contrast between old England's encouragement of various linguistic competences and contemporary monolingual America. Lawrence had spent three years traveling in Syria writing his Ph.D. thesis on crusader castles. He was not alone among British officers in his ability to speak Arabic. He was fortunate, perhaps, that the proliferation of dialects prevented his learned Arabic from exposing him as an Englishman. In the following excerpt he has some fun with his own abilities, in the context of Auda, the leader of the expedition against Akaba, chanting on dark nights to guide his comrades through unfamiliar territory:

"On this long journey Sherif Nasir and Auda's sour-smiling cousin, Mohammed el Dheilan, took pains with my Arabic, giving me by turn lessons in the classical Medina tongue, and in the vivid desert language. At the beginning my Arabic had been a halting command of the tribal dialects of the Middle Euphrates (a not impure form), but now it became a fluent mingling of Hejaz slang and north-tribal poetry with household words and phrases from the Limpid Nejdi, and book forms from Syria. The fluency had a lack of grammar, which made my talk a perpetual adventure for my hearers. Newcomers imagined I must be the native of some unknown illiterate district; a shot-rubbish ground of disjected Arabic parts of speech. However, as yet I understood not three words of Auda's...."

As we continue to struggle, today, with finding the right relationship with our middle eastern neighbors, Lawrence's great account of an early twentieth century collaboration, and a great betrayal, might just possibly contain a few lessons from which we might profit.

Friday, January 20, 2017

From the preface to The Third Crusade

In the year of the Incarnate Word of our Lord 1187, when Pope Urban III held the government of the Apostolic See and Frederick I was emperor of Germany; when Isaac II was reigning at Constantinople, Philip II in France, Henry II in England and William II in Sicily, the Lord's hand fell heavily on His people, if indeed it is right to call those "His people" whom uncleanness of life and habits, and the foulness of their vices, had alienated from his favor. Their licentiousness had indeed become so flagrant that they all of them (casting aside the veil of shame) rushed headlong in the face of day into sin.

It would be a long task, and incompatible with our present purpose, to disclose the scenes of blood, robbery and adultery which disgraced them (for this work of mine is a history of deeds and not a moral treatise); but when the Ancient Enemy had diffused, far and near, the spirit of corruption, he more especially took possession of the lands of Syria and Palestine, so that other nations now drew an example of uncleanness from the same source which formerly had supplied them with the elements of religion. For this cause, therefore, the Lord, seeing that the land of His birth and place of His Passion had sunk into an abyss of turpitude, treated with neglect His inheritance and suffered Saladin, the rod of His wrath, to put forth his fury to the destruction of that stiff-necked people; for He would rather that the Holy Land should for a short time be subject to the profane rites of the heathen than that it should any longer be possessed by men whom no regard for what is right could deter from things unlawful.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)